From Stage to Live Broadcasts and Streaming

September 27, 2016

At the inception of the sound era Eugene O’Neill wrote George Jean Nathan expressing the hope that “the day may come when there will develop a sort of Theatre Guild ‘talky’ organization that will be able to rely only on the big cities for its audiences.”[i]

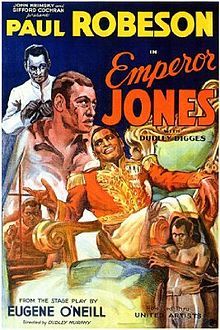

Unfortunately, during O’Neill’s lifetime film was primarily a form of mass entertainment, with inevitable pressure to appeal to the lowest common denominator and to cast bankable stars. The consequent artistic constraints were compounded by the Production Code.[ii] Moreover, feature films rarely exceeded two hours in length.[iii] The Long Voyage Home,[iv] based on the one-act sea plays, succeeded within these constraints[v] and received O’Neill’s approval.[vi] However, Strange Interlude[vii] and Mourning Becomes Electra,[viii] movies based on works epic in length[ix] and problematic in content,[x] are considered abortions.[xi]

Beginning in the 1970’s, though, O’Neill’s plays tended to reach the screen, large or small, in curated series for discerning niche audiences, which is presumably what O’Neill had in mind when he wrote George Jean Nathan of his hope for a Theatre Guild-like organization “able to rely only on the big cities for its audiences.”

On television, O’Neill’s dream has been partially realized. PBS’s “Great Performances” and “American Playhouse,” have presented A Touch of the Poet, Beyond the Horizon, Mourning Becomes Electra, and Strange Interlude.[xii]

Until recently, the closest that movies have come to the sort of production and distribution entity O’Neill had in mind was the America Film Theatre. Over its two seasons, 1973 to 1975, AFT presented films based on over a dozen plays, including The Iceman Cometh,[xiii] to subscribers in 400 cities and 500 theaters.[xiv] Unfortunately, AFT is remembered now as much for the brevity of its existence as for the reach of its ambitions and the excellence of its productions.

Is the Theatre Guild model envisioned by O’Neill and briefly realized by AFT simply not viable, or have intervening advances in technology significantly changed the game? For the allied art of opera, the latter appears to be the case. “The Met: Live in HD” transmissions reach more than 2,000 venues in 70 countries, are shown later on PBS, and a number of them have been released on DVD.[xv]

The most promising theater venture following this updated Theatre Guild model is “National Theatre Live.” Since 2009, NT Live’s more than 40 productions have been seen by over a million people in 2,000 venues, with Benedict Cumberbatch’s Hamlet alone bringing in 550,000 “theater-goers.” Although the series carries the National Theatre brand, the plays are also staged by other eminent theatre companies and producers, including the Donmar Warehouse, Young Vic, London’s West End, and with Of Mice and Men in 2014, Broadway.[xvi]

Will these new methods of distributing filmed plays be good or bad for “real” plays? As ever, opinion is divided.[xvii] Uncharacteristically, O’Neill would seem to counsel us to look on the bright side. In that same letter to George Jean Nathan, he said, “As for the objection to the ‘talkies’ that they do away with the charm of the living, breathing actor, that leaves me completely cold. ‘The play’s the thing,’ and I think in time plays will get across for what their authors intended much better in this medium than in the old.”

[i] Eugene O’Neill to George Jean Nathan, Nov. 12, 1929, in As Ever Gene: The Letters of Eugene O’Neill to George Jean Nathan, ed. Nancy L. Roberts and Arthur W. Roberts (Rutherford, N.J.: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 1987), 102. Interestingly, the Theatre Guild did not produce O’Neill until 1928, the ninth year of the Guild’s existence and less than a year before he wrote Nathan extolling the Guild model for movies. Then, the Guild premiered Marco Millions and Strange Interlude in the same month at different theaters. The Guild first took to the road for the 1927-1928 season. Walter Prichard Eaton, The Theatre Guild: The First Ten Years (New York: Brentano’s, 1929), 34, 101-108, 111-115.

[ii] See Stephen Tropiano, Obscene, Indecent, Immoral, and Offensive: 100+ Years of Censored, Banned, and Controversial Films (New York: Limelight Editions, 2009), Appendix D, “The Motion Picture Production Code (1930),” 271-275.

[iii] Randy Olson, “Movies Aren’t Actually Much Longer than They Used to Be.” Michigan State University: Spartan Ideas (Spartanideas.msu.edu/2014/01/25), accessed 8/24/2016.

[iv] The Long Voyage Home, dir. John Ford, 105 min., Argosy Pictures, 1940.

[v] See, e.g., John Orlandello, O’Neill on Film (Rutherford, N.J.: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 1982) 89-102; Zander Brietzke, American Drama in the Age of Film (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2007), 35-50; William L. Sipple, “From Stage to Screen: The Long Voyage Home and Long Day’s Journey into Night.” Eugene O’Neill Society Newsletter, vol. VII, no. 1 (Spring 1983).

[vi] See, e.g., Robert M. Dowling, Critical Companion to Eugene O’Neill (New York: Facts on File, 2009), vol. II, 595.

[vii] Strange Interlude, dir. Robert Z. Leonard, 109 min., MGM, 1932.

[viii] Mourning Becomes Electra, dir. by Dudley Nichols, 173 min., RKO, 1947.

[ix] Not including dinner breaks, Strange Interlude ran 4 hours, 15 minutes, and Mourning Becomes Electra, 5 hours, 30 minutes. Robert M. Dowling, Eugene O’Neill: A Life in Four Acts (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2014), 340, 389.

[x] Ibid., 345, 390.

[xi] See, e.g., Orlandello, op cit., 38-50, 103-115.

[xii] Burton L. Cooper, “Problems in Adapting O’Neill for Film,” in Richard F. Moorton, ed. Eugene O’Neill’s Century: Centennial Views on America’s Foremost Tragic Dramatist (New York: Greenwood Press, 1991), 82-84.

[xiii] The Iceman Cometh, dir. John Frankenheimer, 239 min., 20th Century Fox, 1973.

[xiv] See Michael Barrett, “American Film Theatre,” Pop Matters, July 17, 2008 (popmatters.com/column/american-film-theatre/PO), accessed 8/26/2016; Raymond Benson, “Remember . . . The American Film Theatre!” Cinema Retro, April 16, 2009 (Cinemaretro.com/index.php?/archives/3150-remember-the-american-film-theatre), accessed 8/26/2016.

[xv] Metopera.org/About/The-Met, accessed 8/23/2016.

[xvi] ntlive.nationaltheatre.org.uk/about-us, accessed 8/26/2016.

[xvii] Preliminary research indicates that NT Live broadcasts generated “greater, not fewer, audiences at the National Theatre” itself and that NT Live “is likely to have boosted local theatre attendance in neighborhoods most exposed to the programme.” (nesta.org.uk/publications-estimating-impact-live-simulcast-theatre-attendance-application-london-national-theatre), accessed 8/24/2016. However, Michael Kaiser of the Kennedy Center asked whether the baby-boom generation could be the last to attend live, fully professional performances. He further suggested that the allure of being able to broadcast to huge numbers could make organizations using digital technology risk-adverse and lead to the collapse of regional theatre. Lyle Gardner, “Why Digital Theatre Poses No Threat to Live Performance,” Manchester Guardian, January 17, 2014.